Lpuresi, Jeneria and Lkasian pose for a picture. All are part of the Warrior Watch team @Kristan A. Norvig Photography

We are pleased to announce that a journal article evaluating our Warrior Watch (WW) Programme has been published. The paper demonstrates that local people were significantly more likely to report positive changes in their attitudes and tolerance towards lions since the inception of Warrior Watch, and to attribute these changes to the programme.

“Promoting human-wildlife coexistence is one of the most complex and pressing global conservation challenges faced today, particularly for large carnivore species,” states the paper’s abstract published in the journal Biological Conservation. Yet there isn’t enough research evaluating whether and how programmes like ours work.

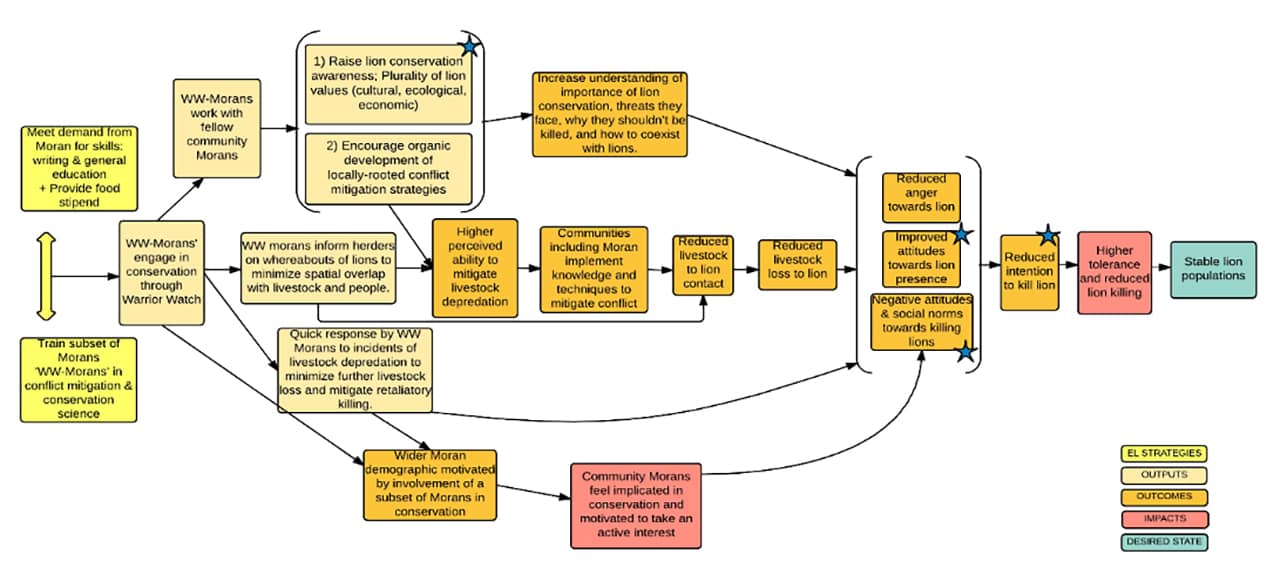

Our Warrior Watch programme draws on the traditional role of young Samburu men aged 15-30 as protectors of their families’ livestock to mitigate human-lion conflict peacefully, as demonstrated by the detailed theory of change below.

The research done examined the impact of Warrior Watch in terms of attitudes towards lions, and towards killing lions (in retaliation for livestock loss), using their intentions to kill as proxy to understand their tolerance level.

It’s exciting to see clear results showing positive changes in people’s attitudes and tolerance towards lions since the inception of Warrior Watch. It is equally important that the paper has been able to demonstrate that evaluations tailored to local capacities and resource-limited situations can produce robust insights to support adaptive management.

The evaluation results justify further investment in the WW programme, as limited resources available need to be invested in work that has real impact. Since the study was conducted in 2017, our programme has grown significantly. This includes geographically, in terms of numbers and in relation to our approach. In 2020, all the warriors of their generation graduated to junior eldership. They are known as the Lkishami age group. In keeping with the culture, eight warriors in our Warrior Watch programme retired, and in 2021, we took on eight new young warriors who had just transitioned in colourful ceremonies across the landscape. Speaking to the new generation, some of the Kasieku warriors believe themselves to be even more tolerant and invested in conservation than the founding generation of Warrior Watch, which has been heartening and exciting to witness. While these anecdotes are important, it is critical for further evaluation to be conducted to understand the impact of these changes over time.

Letoiye, Lpuresi and Yesalai walk forward. They were a part of the original Warrrior Watch cohort surveyed ©Antony Allport

We’d like to thank lead authors Alexandre Chausson, and our then conservation manager, now advisory board member Heather Gurd for their tireless efforts in ensuring a rigorous evaluation was done. The founders of this work, Dr. Shivani Bhalla and Jeneria Lekilelei, and our team including Toby Otieno, Ben Lejale and Peter Lenasalia were instrumental in providing data and advice as the paper was conceptualised and took shape. Special thanks to Prof. E. J Milner Gulland for her guidance and advice throughout the journey to publication.

The longevity and success of the Warrior Watch programme would not be possible without the incredible and sustained support of the Whitley Fund For Nature, National Geographic Society, Houston Zoo, and the Wildlife Conservation Network.